A few weeks ago Daniel called me into his office to see a patient who had come to the clinic complaining of shortness of breath. Sitting on the bench was a middle-aged woman with a huge tumor growing out of her neck. It was pressing on her throat, thus making it almost impossible to breathe. While there are many people who come to our health center with enormous goitres from lacking iodine this one was different. Daniel drained it and was fairly confident that it was cancer and if not removed soon, probably going to kill her.

When patients need care that is beyond what we can provide they either go to Bonga, about 45 minutes away, or the larger city, Jimma, four hours away. Daniel knew she would need more serious help and therefore brought her to see the health center director who would help her figure out the next steps to get her to the hospital in Jimma. We advised her to return to her town and request a “free letter” (when people are very poor the village chairman can write them a “free letter” which attests to their need to have treatment given at no cost), gather some money for her journey and to come with us to Jimma the following week. We weren’t exactly sure what date the car would be leaving so we collected her contact information and said we would be in touch once we knew for certain.

A few days later I was in her village on outreach and sent her a note letting her know that a car from Lalmba would be going to Jimma in four days. (Keep in mind that I am using my very limited Kafanono and hand gestures to explain who I was looking for). As I have written about in other posts, proper communication here is painfully lacking....with no home phones, cell phones, mail, home addresses or internet we often have to rely on letters passed on from one person to the next in order to communicate. As I have seen in other situations and again here-- it doesn’t always work so well.

Three days later a woman did in fact arrive in Chiri with a large neck tumor and eager to see what the doctors in Jimma could do for her. Unfortunately, she was not the same woman! Our note must have been given to the wrong person.... The lady did have a huge goitre for over 15 years and while we don’t typically take goitre patients to Jimma (its not life threatening) it seemed like it was the right thing to do considering the circumstances. Ironically, she didn’t have a free letter and so would have to return home and come back with one for our next Jimma run. So thus, we went to Jimma without any woman or any neck tumors.

Luckily, the real patient returned a week later, still breathing and ready to go to Jimma. Free letter: check. Family member to escort her: check. Correct tumor: check.

Ahhh, the pleasure of working in the developing world.

Daniel and I will be spending a year living and working in rural Ethiopia, at the Chiri Health Center. It will indeed be a year of many firsts--- we are concluding (as of yesterday) our first full year of marriage and starting our first time living abroad together, working together, and so much more than I can imagine as I type this from our first home in Ann Arbor, Michigan. August 10, 2010

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

It's got to be tough

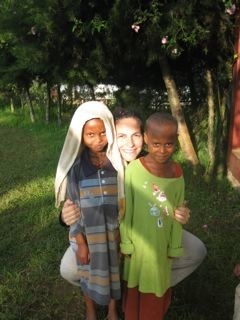

As I have written about in the past, there are 13 children living at Lalmba. Some are true orphans while others have a parent but for whatever reason they are not able to care for them. I think it is safe to say that they may be 13 of the most talented, smart, beautiful and all-around amazing children in the world. They are always eager to help (literally running up to the car every time we return from the market or with a new visitor), they love learning new things, they seldom complain and they are always happy to dance, draw, braid your hair, play a game, cook...and just about anything.

I have found that the kids can put a smile on my face no matter how rough my day has been, and that overall they are a huge reason why our stay in Ethiopia has been so great. All I need to do is walk down the hill to the children’s home and seeing them run up to me with with their arms flailing automatically puts a smile on my face. I have been struck several times at how mature and good natured they are, whether it’s helping translate for me or their excited willingness to work on a new project (such as the mountain bike trail they recently built with Daniel). Every week or so I try to bring them up to our house to bake something yummy. I wish you could see how patient they are, all 13 of them mind you, while they each get a turn to pick out and mix one ingredient. They don’t complain, grab, yell or fight over who gets to crack the egg or add the chocolate chips...they all leave smiling and happy to take part in what I think most American kids would think was slow, boring and dull.

Lalmba’s goal with the kids is not to have them adopted into American or Ethiopian homes as a few people have asked me. Rather, Lalmba sees them as the future of Ethiopia and aims to give them the resources (mostly by way of a stable home, basic life skills and extra tutoring) needed to make sure they succeed in life. They are all exceptionally bright and I have no doubt that they will pass the exams needed to get into university here.

Overall, they are happy and healthy children who laugh and smile often, get good grades and basically are no different than any other Ethiopian kids in the village. I can’t help but think that even with the benefits they get from living here, it’s got to be tough. What I can’t seem to get out of my mind is that they are, for all practical purposes, orphans-- they don’t get to run into their moms’ arms when they come home from school, they will never know what it’s like to crawl in bed with their parents or be able to see their parents’ smiling faces when they graduate from high school or college.

Just today one of the youngest girls, Italey (it-ah-lay), had something wrong with her eye. I brought her to see Daniel and after some poking around her eye ultimately he had to irrigate it. During all this she was crying and was obviously in a lot of pain. I went to check on her just now and she was still not feeling up to speed. Her eye was still hurting her and you could just tell she felt like crap. It’s moments like these that I realize how unfair it all is. While I was able to hold her hand during the procedure and give her a hug just now when I checked on here it’s still not the same as what a mom or dad can do for a sick kid just by being there. I offered her water and other than that knew I had to just let her be....no silly game or piece of candy could make her feel better. I’m sure soon enough she will be her usual perky fun self, but in the mean time I’d say that it’s got to be tough.

Thursday, February 3, 2011

What's The Right Thing To Do?

On Wednesdays and Fridays, with three other Chiri Health Center staff members, I visit one of the ten villages to which we provide immunizations. It’s a real perk for me as the drive and hikes are all amazingly beautiful and it allows me to spend time in the local communities. Vaccinations have been a large part of our public health program since Lalmba began working in Chiri twelve years ago. A few years ago the Ethiopian government started a community health worker program that assigns one or two health workers (called Health Extension Workers, or HEWs for short) to every village. They are trained to give vaccines, assist in deliveries, provide family planning, and other general health promotion activities. Community health worker programs are not uncommon and have worked really well in some countries, improving maternal and infant mortality and sanitation-sensitive illnesses.

Unfortunately we have found the HEW program in our area to be less than ideal. The workers are often young, placed in very rural communities far from family and friends, and are seemingly somewhat unmotivated to do their assigned tasks. It seems that in many cases the HEWs spend a substantial amount of time in Chiri (a relatively large village) rather than in their assigned, more remote villages. Frequently, when we show up to outreach to do vaccinations they are no where to be found and had not told people in the community that we would be coming.

I held a big meeting with all the HEWs who serve in our target areas and the village chairpersons to talk about the vaccination program. I made it clear that from now on the HEWs had to be there when we were scheduled to be in their village, both to help give the vaccines but more importantly to keep track of the records (if both the HEWs and Lalmba are giving vaccines without coordinating, there is a good chance we are over vaccinating people, which is not good). It was a very productive meeting where both their concerns and ours came out and solutions were found. I made it clear that if we showed up and the HEW was absent we would turn around and go home, no vaccines would be given. Unfortunately, the very next day and again last week we showed up to outreach and no one was there.

So here is where the predicament comes up, do we continue to provide vaccines in these areas where the government has its own program to be doing it? Are we enabling these workers to not do their job by our continued presence? While it would be easy to understand why we would drop the program altogether (even though the HEWs are adamant that they want us to come) there is a good chance that the people who would be most affected are the community members who would no longer get vaccinated. It seems like this is the big dilemma for all types of development/nonprofit work- even though the work may positively affect people, in the long run is what we are doing causing more harm than good?

Friends were recently here visiting and this question came up. Is it ever okay for outsiders (i.e., white, American, educated folks like us) to work in a country like Ethiopia? Is our presence here imperialistic? To me it is a very grey area, with no obvious right or wrong answer. There are days when I really question our presence here. Yet on others where I feel very confident that our being here is beneficial. After-all, by being here, we’re able to bring some of the training and skills that we’ve been fortunate enough to receive and that are not yet available to the local community. I think the vaccine situation is a good example of this dilemma. On the one hand, we are able to vaccinate thousands of people each year against diseases that might otherwise kill them. On the other hand, we are doing a job that someone else, i.e., the government, should be doing (which is the case with many other issues that NGOs work on all over the globe -- building schools, hospitals, orphanages, doing advocacy work, etc). Is there ever a situation for which it is permissible for outsiders to work? What about university professors who teach abroad? Engineers or doctors who come to the US to work? Is there a difference when it is people from one developed country going to another developed country versus developed to underdeveloped?

I am curious to know what your thoughts are on this...where do you weigh in on this complicated issue? Any comments are greatly appreciated!

Sunday, December 19, 2010

The Little I've learned So Far

As I have written in other posts, I am continually amazed at how strong and supportive communities appear to be here. Just last night Daniel told me about a young child that was brought in after being bitten by a baboon. I haven’t seen any baboons around our area so I asked where they came from. Turns out they were from Angola, nothing less then a twelve hour walk. So what means is that about twenty or so friends and family members made a stretcher and took turns carrying this kid up and down windey roads, barefoot, without water, Powerbars, Gatoraid, or really anything that you or I would bring on even a leisurely hike. Just to give you a sense of how difficult this must have been, when we went to this area for outreach there were points where I wasn’t sure our “super-duper can get over anything tank” Landcruiser would make it.

So why I am telling you all this?

Unfortunately I found out recently that someone in my family was diagnosed with a pretty rare tumor. At first they thought it was in the lung which would require opening up the chest to remove it but after a second opinoin it was actually found to be on the pericardium. A tumor on the pericardium is extremely rare, so much so that they have no idea what the chances are of it being benign or malignant. On the flip side, it means that the surgery no longer involves opening the chest (which is pretty invasive and difficult) but can be done thropscopically, which allows for a much easier recovery.

Obviously being a zillion miles, time zones and without good cell or internet connection makes this a pretty difficult situation. I can’t be at the doctor’s appointments or able to give good moral support. At the most recent appointment with a highly respected surgen he said that because the surgery no longer requires opening the chest it wasn’t necessary for family to come in from overseas. No, this would be routine, in and out in a day or two with a recovery time of up to two weeks. And as it goes in the US, If she needs some help afterwards making food, getting to a follow-up appointment, filling a prescription.....well, hiring someone is always a possibility.

Perhaps being here for four months has had a stronger impact on me then I first thought because his response seems just absurd to me. At our clinic when we transport patients to bigger hospital we have to fight with families because they all want to come with. I’ve seen patient’s families wait patiently for days and weeks by their loved one’s bed with little more to do then stare at the walls (no wifi, tvs or magazines in these parts). When a patient needs to go to a bigger hospital we make sure they have enough money to pay the hospital fee and get transportation home, which can be no less then a year’s income. I’ve seen people tell us there is no way they can come up with that amount of money, and somehow their community is able to come together to sell a cow or collect from one another the necessary amount.

Everyone said that coming here would be a great learning experience and I can’t help but feel like I am being given the ultimate test right now. Yes, I can listen to this doctor and tell myself that its not worth coming home. The money, the time, the inconvenience--- all add up to being there not worth it I suppose for him. If I go home, it will mostly likely mean we can’t go on the trip to Tanzania we were hoping to, my work plan will have to be adjusted and people at the clinic will all have to pitch in to fill in for my absence. Are these the types of things the doctor was thinking about when we said returning was not necessary? Maybe its more that he only thinks of the physical surgery and nothing else.... not the emotional side that comes with being sick. I feel confident that the surgery will be fine, but what about everything else? Don’t people need their family to help them through the scared feelings, the worry, the anxiety?

I can’t help but think about the different things here that might seem so absurd to people back home; from having chickens living in your house to the necessity of collecting firewood in order to cook dinner. And yet I think what this doctor is suggesting would be equally shocking to my friends and colleagues here. Not being with your loved one in a time of need like this and paying someone else to help them....I just don’t think people would even be able to fathum this as being a possibility. When someone is sick, everyone pitches in.

While being here had taught me a lot about public health, malnutrition, driving a stick shift, etc. I think the biggest lesson I have learned is that you should do anything and everything for your family and friends...that you should treat people the way you want to be treated. If it was me I would want everyone to drop what they were doing, put off vacations, reschedule meetings and be by my side. So contrary to what this doc said, I will be coming home to be with my mom while she watches tv and runs errands(anything really to keep her mind off of this) leading up to the big day, be waiting in the hospital while the surgery is taking place, have her favorite meal ready for her when she wakes up and make sure she has all she needs when she goes home. It’s funny that we often think as the developing world as being “behind” and yet in a situation like this they seem to make us look like we have it all backwards.

So why I am telling you all this?

Unfortunately I found out recently that someone in my family was diagnosed with a pretty rare tumor. At first they thought it was in the lung which would require opening up the chest to remove it but after a second opinoin it was actually found to be on the pericardium. A tumor on the pericardium is extremely rare, so much so that they have no idea what the chances are of it being benign or malignant. On the flip side, it means that the surgery no longer involves opening the chest (which is pretty invasive and difficult) but can be done thropscopically, which allows for a much easier recovery.

Obviously being a zillion miles, time zones and without good cell or internet connection makes this a pretty difficult situation. I can’t be at the doctor’s appointments or able to give good moral support. At the most recent appointment with a highly respected surgen he said that because the surgery no longer requires opening the chest it wasn’t necessary for family to come in from overseas. No, this would be routine, in and out in a day or two with a recovery time of up to two weeks. And as it goes in the US, If she needs some help afterwards making food, getting to a follow-up appointment, filling a prescription.....well, hiring someone is always a possibility.

Perhaps being here for four months has had a stronger impact on me then I first thought because his response seems just absurd to me. At our clinic when we transport patients to bigger hospital we have to fight with families because they all want to come with. I’ve seen patient’s families wait patiently for days and weeks by their loved one’s bed with little more to do then stare at the walls (no wifi, tvs or magazines in these parts). When a patient needs to go to a bigger hospital we make sure they have enough money to pay the hospital fee and get transportation home, which can be no less then a year’s income. I’ve seen people tell us there is no way they can come up with that amount of money, and somehow their community is able to come together to sell a cow or collect from one another the necessary amount.

Everyone said that coming here would be a great learning experience and I can’t help but feel like I am being given the ultimate test right now. Yes, I can listen to this doctor and tell myself that its not worth coming home. The money, the time, the inconvenience--- all add up to being there not worth it I suppose for him. If I go home, it will mostly likely mean we can’t go on the trip to Tanzania we were hoping to, my work plan will have to be adjusted and people at the clinic will all have to pitch in to fill in for my absence. Are these the types of things the doctor was thinking about when we said returning was not necessary? Maybe its more that he only thinks of the physical surgery and nothing else.... not the emotional side that comes with being sick. I feel confident that the surgery will be fine, but what about everything else? Don’t people need their family to help them through the scared feelings, the worry, the anxiety?

I can’t help but think about the different things here that might seem so absurd to people back home; from having chickens living in your house to the necessity of collecting firewood in order to cook dinner. And yet I think what this doctor is suggesting would be equally shocking to my friends and colleagues here. Not being with your loved one in a time of need like this and paying someone else to help them....I just don’t think people would even be able to fathum this as being a possibility. When someone is sick, everyone pitches in.

While being here had taught me a lot about public health, malnutrition, driving a stick shift, etc. I think the biggest lesson I have learned is that you should do anything and everything for your family and friends...that you should treat people the way you want to be treated. If it was me I would want everyone to drop what they were doing, put off vacations, reschedule meetings and be by my side. So contrary to what this doc said, I will be coming home to be with my mom while she watches tv and runs errands(anything really to keep her mind off of this) leading up to the big day, be waiting in the hospital while the surgery is taking place, have her favorite meal ready for her when she wakes up and make sure she has all she needs when she goes home. It’s funny that we often think as the developing world as being “behind” and yet in a situation like this they seem to make us look like we have it all backwards.

Monday, December 13, 2010

Africa Is Not A Country

When I first thought about coming to Ethiopia I expected a dry, brown, sad place where life was difficult and hard and anything but enjoyable. I would venture to guess that when most people think about Africa there is little positive that comes to mind. From movies, magazines, newspaper articles and books, I have found there is little positive said about this large and diverse continent (which is often lumped into one place, “Africa”, and rarely its individual countries). Daniel is in the middle of one of these books, where the only things discussed are how terrible everything is here-- the corruption, the poverty, how NGO’s have destroyed people’s work ethic, the spread of HIV, etc.

I can’t help but think back to an assignment I was given in graduate school to do a community needs assessment of the Delray neighborhood in Detroit. My professor wisely told us that we were to look at the area’s strengths--not to focus only on the problems. As those of you who are familiar with Detroit know, it would have been very easy--and most likely what we would have done. Only focus on the bad....the run down houses, the boarded up buildings, the liquor stores and miss what positive things were very much there but easily overlooked when going in with a negative mindset, the houses with beautiful gardens, the churches, an active community center, etc.

While I am sure that all the bad things people write about and highlight in movies about Africa are true for some people, it is for sure not the case for everyone. Where we are in Chiri, I am often times jealous of the life that people have here. Children grow up in green, lush mountains able to run around and play without worries, families are unbelievably close, people will go to great lengths to help others (even if it means carrying a neighbor who is in labor on a stretcher up mountain roads for up to eight hours in order to get to a doctor), because no one has a car people walk everywhere giving them ample opportunity to spend time with friends and family, there isn’t the constant advertising of products and things that can make you feel like you never have enough...the list could go on but I think you get my point. Of course there are a lot of hardships that come with living in a developing country like Ethiopia-- the chances of dying from a treatable illness is huge, people don’t have a ton of opportunities for a meaningful career, most people can’t turn on the tap to get water or have a stove to cook.

While I realize no situation is black and white and that neither place is better then the other, I can say without a doubt in my mind that Ethiopia is an engaging country with beautiful, happy and generous people which turns any assumptions about what “Africa” is on it’s head. I just wish there were more journalists and filmmakers that saw the other side that exists here. I wish there were articles about the families who sit by their loved ones beds and bring them food for days on end while at the clinic, or the parents who carry their children for hours, and even days in some cases, when they are malnourished. I wish there were movies about the many families who are surviving just fine working their fields and don’t rely on food aid. I wish there were NY Times articles about people who work hard, go to college and work in places like our clinic helping their community. I wish there were films that conveyed how green and mountainous and lush this country is. I wish the news told the story of the men and women who are entrepreneurs who are growing towns like Chiri.

What I really wish is that you could see all this for yourself....I don't think that this blog can give justice to all that I have seen and felt in just the short time I have been here. I do wonder though why this is the case....is there something we get out of labeling places like Ethiopia as poor and in need of saving? Why don't we hear more about all that is positive here?

(If you are wondering where the title to this blog comes from, a classmate in social work school wore a button with “AFRICA IS NOT A COUNTRY” which really amused me)

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

What Makes a Day Great?

Today was a typical day for me here at Lalmba. I set out early to go on outreach to the village of Angela, a newer site for us, which was a two hour drive from Chiri. Turnout was good and we gave over 200 hundred vaccines. We were there most of the day and returned to the health center around 3pm. I was sitting in my office when Faith told me that one of my favorite malnutrition patients, a little girl named Mizrat, had returned with her father for her follow-up appointment. As I have mentioned in other posts, I spend a lot of time in the malnutrition room playing with the kids and interacting with the parents. They are here from one to two weeks, depending on how bad their case is, so it gives me a god opportunity to get to know them. There was something really special about Mizrat and instantly I just adored her. When she first came to Lalmba she could barely walk, I should mention she is two and a half, and was in such bad shape that she basically couldn’t do anything but sit in her bed all day. Slowly but surely her health improved was and she became more active, walking all around the clinic with me (my version of physical therapy I guess) and began to actually interact with the world around her. When her time here ended I sadly said goodbye to her father and her, hoping they would return for follow-up so that I could see them again. Patients can live very far away, theirs is a six-hour walk, so it’s not a sure thing that they return.

I was glad to hear that they came back for their appointment but was a bit said to have missed them. Faith said they waited a bit but must have left. Bummer…..I was wondering how she was doing and if she would remember me, but I would have to be satisfied with just reading her follow-up paper work.

As I was imputing data from today’s outreach one of the clinic guards came into my office to say that my friend was here. I looked and up and wouldn’t you know—it was Mizrat!! Her father said that he really wanted to see me so they spent the afternoon in town (not sure what they could have done since there isn’t much to do here). Literally in a matter in seconds my day went from fine, to amazing. I really can’t tell you how happy it made me to see them and to be able to give her a hug and see them for a bit. I must have had the biggest smile on my face and I think I yelped with delight when I saw it was them. There happened to be another patient and her father here for malnutrition follow-up, so the four of us chatted for a bit. Something new I am starting here is to give patients who return for follow-up seeds to plant vegetables in their gardens. People here mainly grow and eat cocho and teff, plants that don’t provide enough protein or calories which causes malnutrition. While patients are here we counsel them on different foods, show them our demonstration garden and have them attend a cooking class all in hopes of teaching them about the different foods that can be grown here--carrots, beets, spinach, etc. (Unlike in the US where people often know how to prevent diseases, here surprisingly people have no idea that their diet can cause malnutrition.) I gave the fathers some seeds and tried to pick their brains on how to make the program better. While they didn’t have any criticisms of the program Mizrat’s father did have a lot to say about why it was good.

Before coming people in his town said he was crazy to bring Mizrat to Chiri as it was obvious she was going to die. No one thought she would make it and the journey would be for nothing. He came anyway and sure enough she was not only alive but doing better. When he returned home everyone was so happy and excited to see that she was in fact alive and well. He went on to describe how he learned here how to change their eating to make sure this doesn’t happen again and about other health issues that can cause illnesses such as poor sanitation, cleanliness, etc. Clearly, the health center had done a lot for Mizrat and he was tremendously grateful as he came with only 35 birr (about $3) and Lalmba paid for all of her treatment and his food while they were here. He thanked us and promised to be back for his last check-up in a few weeks.

There are moments when I wonder if the work I am doing here really matters. I can’t help but question if the communities I go to on outreach would be any different if I (or any other ex-pat) wasn’t here….and if there is any real change from the work we are doing. But then there are times like this afternoon when the sight of Mizrat and her father just made my day. Knowing that they stayed to see me makes me think that the little itty bity part I play here might just matter after all.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Being Poor Sucks

As the day was ending at the clinic I noticed Daniel and Richard, the other ex-pat doctor, walking into an office with their last patient. Seeing as I had just finished up with my work I thought I would sit in. The young man looked pretty healthy but as it turns out he had TB. This is a pretty common illness here, one which is treated with two months of daily medications given at the clinic followed by six months of medication taken at home. The key to treating TB effectively is that the patient cannot miss a dose of their medication and if he or she does the infection can become drug resistant which is really bad-- therefore we initially require patients to stay in town and come to the clinic each morning to take their meds. If you have read Tracy Kidder’s book about Paul Farmer, Mountains Beyond Mountains (which I highly recommend) this probably rings a bell.

Anyway, the patient was about 17 years old and from a village very far away. When it was explained to him that he had TB and what the treatment protocol involved, he got a very sad look on his face. While you might guess this was due to the new information about having TB, the truth was that he was more stressed about how much it would cost for him to be able to stay in town to be treated. He explained to us that last year his family and he had been moved from another area of the country and resettled to our zone because of the limited amount of land where he is from. We sat there listening to him as he told the story of his family’s finances, they used to have more money but now are quite poor, and how he now only has 50 birr to his name (about $4). He quickly calculated how much it would cost him to rent a room for the two months and to buy food, less then $15 a month, and immediately his head sunk. This was too large an amount, impossible for him to come up with. Could he go home and borrow money from family and friends we asked? He did not seem too optimistic about this. Could he start treatment today he wondered? He clearly understood the danger of TB and wanted to start medication as soon as possible.

Normally we require a 75 birr deposit, but all he had was 30 birr. Lalmba does have a special fund for people who truly cannot afford their treatment, but I had a feeling he might not qualify. This may sound crazy but since he had shoes and new(ish) pants and a shirt I had a feeling the committee that decides these cases wouldn’t believe him. Now whether he can come up with the money or if the committee will find him needy enough to pay for both his treatment and living costs, I don’t know. I don’t think Lalmba would ever let a person go without being treated, especially for something as serious as TB, but the situation still pains me just to think about it. If that were me or probably any one of you reading this blog this would never be our reality. TB is almost nonexistent in the US in the general public largely due to our higher standards of living and better health care, when we need to get from point A to point B it usually doesn’t involve walking for hours or days, most teenagers wouldn’t have to travel and be on their own when seeking health care in a different city, and most obvious--- if we were facing a potentially deadly illness that would cost less than $50 to treat, it would not cause us an unbelievable amount of stress.

Daniel and the other doc, Richard, sent him home to collect his stuff and bring back as much money as he can come up with. TIme will tell what the outcome will be for him as he said he could be back by Thursday (it’s about a day’s walk from Chiri to his town).

Everyday we see patients like this and the same thoughts run through my head. Whether it’s a child who is so severely malnourished they look as if they just left a concentration camp, or a woman who was burned after having an epileptic seizure and fell into the fire they use for cooking, it all just seems so unfair. So much of the illness and injury we see is completely avoidable it really makes you wonder if life is playing a mean joke on so many billions of people whose reality is like this patient.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)